- Home

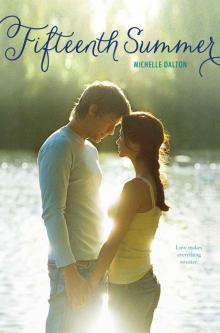

- Dalton, Michelle

Fifteenth Summer Page 4

Fifteenth Summer Read online

Page 4

This was the part where I was supposed to groan and make a joke about two bad similes in one sentence.

But instead my throat seemed to close up as I realized something—

I was reading to my new crush from a summer romance novel. It was about as subtle as my sticky-chin check.

Okay, I told myself. I tried to take a deep breath without appearing to take a deep breath. Maybe he’s not making the connection. He’s a boy, and lots of boys are clueless. Or maybe he isn’t clueless but he just doesn’t associate me with a summer romance at all.

How could I figure out which one it was? And how could I also find out his name, his age, and whether he’d been on Team Peeta or Team Gale? (Either one was fine, as long as he’d never been on Team Edward or Team Jacob.)

When you were in a bookstore, those were perfectly legitimate things to ask, right? So why was I still speechless?

We were just verging on an awkward silence when Stella’s voice rang out from the front of the store.

“Josh, honey? You back there?”

The boy looked up at the ceiling and sighed quietly before calling out, “Yeah?”

I felt that little flutter in my stomach again.

His name is Josh.

Then the boy spoke again. “What is it, Mom?”

This time my eyebrows shot up.

His name is Josh and his parents own the bookstore of my dreams.

It seemed so perfect that I couldn’t help but grin. My smile was unguarded, uncomplicated, and delighted. I did not have this sort of smile very often. It felt a lot like the smile that had been on Josh’s face a moment ago.

Luckily, Josh was listening to his mother and not looking at me while I grinned like a big goofball. I only half-heard the question she asked him—something I didn’t understand about a packing slip and a ship date.

Whatever it was, it seemed to bring Josh back to the serious worker-bee place he’d been before we’d started talking.

“It’s in the office file cabinet, third drawer down in the back,” Josh called. Then he added, in a mumble, “Where it was the last time you asked.”

He stared at the X-Acto knife in his hand for a moment. I could tell he wasn’t seeing it, though. His eyes were foggy and distant, and they were definitely not too happy.

Then he seemed to remember I was there and looked at me. He pointed at the book in my hand.

“So, are you buying that or not?” he asked gruffly. He was suddenly impatient to get rid of me so he could get back to his book destruction.

And just as suddenly my rescue of Coconut Dreams didn’t seem cute, clever, and boy-impressing. It was silly, a waste of Josh’s apparently very valuable time.

I wondered if I’d been mistaken about his double take. And maybe we hadn’t just had an amazingly easy and fun conversation about his cart full of doomed books. Maybe I’d imagined all that, and in fact I was just another annoying customer at Josh’s annoying summer job.

So now what was I supposed to do? Put the book back and skulk away? If I did, I’d have to sidle past Josh in the narrow aisle. Twice. It’d be much quicker to just make a dash for the front desk.

So I nodded at Josh.

“I’ll take the book,” I said quietly.

“Fine,” he said, looking stony. “I’ll ring it up for you.”

“That’s okay,” I said. “Your mom can do it.”

Josh shrugged—looking a little sulky—and turned back to his cart.

I headed back up the aisle toward the front desk. Just before I emerged from the stacks, I heard the awful sound—rrriiiiip—of another book cover getting slashed.

I couldn’t meet Stella’s eyes as I handed her Coconut Dreams.

“Well!” she said brightly. I nodded sympathetically. What else could you say to such a pathetic purchase? I could have told her the book was supposed to have been a joke between me and her son, but now the joke had fizzled and it was just a cheesy book on clearance that I was buying before I made a quick getaway. But that seemed like a lot to explain, so I just stayed silent.

Why, I asked myself mournfully for the hundredth time, did I take my e-reader into the shower?

“So that’s a dollar ninety-nine,” Stella said. I handed over two of my precious dollar bills, then dug into my pocket for the tax.

“No tax, sweetie,” Stella said. “After all, that book was headed for the shredder. You rescued it!”

“That’s what I said,” I said. She grinned at me, and I half-smiled back, feeling a little less mortified.

“Okay,” I sighed. “Well . . .”

I cast a glance back toward the stacks, where Josh was still hidden. Suddenly I felt a rush of tears swell behind my eyes.

How had this gone so wrong? I wanted to linger in Dog Ear. I wanted to slowly browse the stacks, then take a tall bundle of books over to the lounge. I’d flop into that cracked-leather chair, where I’d skim through six different first chapters while nibbling vanilla wafers. Then I’d buy myself a good book and take it straight to the beach.

But instead I’d met Josh, and somehow we’d gone from flirting to flame-out in less than five minutes. I was too mortified to stay. I had to slink out of Dog Ear, with a lame book, to boot.

It just wasn’t fair.

I turned back to Stella to thank her for ringing me up, but she was peering with concern into the lounge.

“E.B.,” she said with a warning tone.

The dog lifted one eyebrow at her and whimpered.

“Oh, no,” Stella cried. “E.B., hold on, boy!”

She swooped down to reach for something under the counter. When she came up, she was holding a leash.

Now the dog let out a loud, rumbling groan.

“Noooo, E.B.!” Stella cried. She raced over and grabbed the dog by the collar. She clicked on the leash and hustled E.B. to the door.

“You know you shouldn’t eat so many cookies,” she scolded.

I clapped a hand over my mouth to keep from laughing out loud as Stella hustled her rotund black Lab through the door.

But a moment later I felt a presence behind me, and my urge to laugh faded.

It was him. I just knew it.

I paused for a moment before turning around. I inhaled sharply.

You know how some people’s looks change once you get to know them? Unattractive people become better-looking when you find out how funny and smart they are. And gorgeous people can turn ugly if you find out they’re evil inside.

Well, now that I’d seen Josh’s surly, sullen side . . . that didn’t happen at all. He was somehow cuter than ever. Which is really annoying in a boy who’s made you feel like an ass (even if he did make me feel pretty amazing first).

“E.B. has a touch of irritable bowel syndrome,” Josh explained.

“Am I supposed to laugh at that?” I asked.

“No,” Josh said simply. “It’s not a joke. It’s really gross, actually.”

That, of course, made me want to laugh. So now Josh was making me feel like an immature ass.

“Well, I hope he feels better. See ya,” I said. Of course, I didn’t plan to see Josh. I was already wondering how I could find out his work schedule—so I could be sure to avoid him.

“Look at this,” Josh said, thrusting a book toward me. It sounded a lot like an order.

“Excuse me?” I said. I raised one eyebrow, which was a skill I’d learned recently. I’d had a lot of time to practice it during the drive from California.

It worked. Josh looked quite squirmy.

“I mean, well, I think you might like this book,” he said more quietly. When I didn’t take it from him, he put it on the counter next to me. I glanced at it only long enough to see that the cover was still intact. It had a photo that looked blue and watery.

“Listen, Coconut Dreams is not my usual kind of book,” I said. “If this is anything like that, I think I’ll pass.”

“It’s not, I swear,” Josh said. “Look, it’s not even on clearance.�

�

I gave him a look that I hoped was deeply skeptical, and picked up the book.

I loved the look of the cover. It was an undulating underwater photo. In the turquoise water you could just make out a glimmer of fish scales, a shadowy, slender arm, and one swishy coil of red hair.

Beyond the Beneath, the book was called, and oh, did I want to flip through it and find out if the words were as flowy and beautiful as that cover. But I wasn’t about to tell Josh that. He’d already gotten me all confused with his mixed signals and his cuteness. Plus, I only had five bucks left in my pocket, so I couldn’t afford the book anyway. I was going to make my escape while I could.

“I don’t think so,” I said, trying to sound breezy. I tossed the book back onto the counter. “But thanks.”

“Oh, okay,” Josh said. He dug his hands into his pockets and looked away, the way I always did when I was disappointed.

I’m sure that’s not it, I told myself. That’s probably just where he keeps his extra X-Acto knife blades.

Josh seemed to have spotted something behind the counter. I followed his gaze to the receipt paper trailing out of the cash register. It had a bright pink stripe running along it.

“Oh, man,” he muttered. “She never remembers to change the tape.”

He ducked around the end of the counter and started extracting the paper roll from the register, scowling as the thing seemed to evade his grasp.

“Weird,” I said.

Josh stopped fiddling with the receipt tape and looked at me.

“What’s weird?” he demanded.

“I think it would be a dream to work in a bookstore,” I said, “and you don’t seem to like it at all.”

“I like it—” Josh started to say, sounding super-defensive. He stopped himself and frowned in thought. “It’s not that I don’t like it. It’s just that, when people open a bookstore, they think it’s going to be all, you know, books.”

“Isn’t it?” I asked.

“Well, yeah,” Josh said, “but it’s also receipt tape. And packing slips and book orders and remembering to pay the air-conditioning bill.”

“But you don’t have to worry about that,” I scoffed. “I mean, you’re . . .”

“Fifteen?” Josh said. “Yeah, well, you don’t have to have a driver’s license to pay the air-conditioning bill. You just have to have a tolerance for really boring chores.”

At that moment he looked a lot older than a boy my age.

Even though, I couldn’t help noting, he was a boy my age. Not college age or even my sisters’ age.

I don’t know why that mattered to me, though. Who cared if he was age-appropriate? Yes, he was really, really good-looking. And mature. And for about three minutes it had seemed like he thought I was pretty intriguing too.

But now I didn’t know what to think about this boy. How could I have anything in common with someone who found a bookstore—this bookstore—as uninspiring as receipt tape?

And how, I wondered as I walked out the door, could I possibly feel worse leaving Dog Ear than I had before entering it?

That night my dad grilled corn and salmon, and my mom tossed an arugula salad with hazelnuts and lemon juice. Abbie and I collaborated on wildly uneven biscuits. Mine looked like shaggy little haystacks, while hers were perfectly round but as flat as pancakes. Hannah made a fruit salad, then muddled raspberries and frothed them into a pitcher of lemonade.

But instead of setting the table like usual, we piled all the food into boxes and baskets and toted them down the two blocks to the lake.

Sparrow Road was narrow and sharply curved. Though the road was paved with used-to-be-black pavement, walking it meant wending your way around various large cracks and potholes. Before you knew it, you were usually in the middle of the road. Which was fine because there were hardly ever any cars. There was no reason to drive on Sparrow unless you lived in one of the twenty-or-so houses on it.

I always loved our first shadowy walk to the lake. It was so thickly overhung with trees that by August you felt like you were in a tunnel. Of course, by August you also had to spend most of that walk slapping away mosquitoes and horseflies. But even that—after doing it my whole life—felt like a ritual.

I think we all exhaled as we rounded the last bend in the road that led to our “stop.” This was a little wooden deck with a bike rack (not that anybody bothered to lock their bikes here) and a rusty spigot for hosing the sand off your feet. A little gate on the far end of the deck led to the rickety, narrow boardwalk that led to the beach.

None of us spoke as we kicked off our shoes, then walked down the boardwalk single file.

Tonight the silence seemed heavy with meaning and mourning. But actually we were always pretty quiet during our first visit to the lake. After the Pacific, so violent and crashy, the lake seemed so quiet that it always made us go quiet too. As a little kid I imagined that this water kept people’s secrets. Whatever you whispered here was safe. The lake would never tell.

As we stepped—one after another—from the boardwalk onto the sand, I realized that maybe I hadn’t completely outgrown that notion.

After we’d settled onto the sand (nobody had had the extra arm for a picnic blanket) my mother declared, “Dinner on the beach on our first night in Bluepointe. It’s a new tradition.”

Even though her voice caught on the last syllable and her eyes looked glassy in the light of the setting sun, she smiled.

I gave her my own damp-eyed smile back. It felt weird to be simultaneously so sad without Granly and so happy to be there in that moment. The smoky, charred corn was dripping with butter and the sand was still warm from the sun, which had become a painfully beautiful pink-orange. The gentle waves were making the whooshing sound that I loved.

When I’d finished my salmon and licked the lemony salad dressing from my fingers, I got to my feet. I scuffed through the sand, tiptoed over the strip of rocks and shells that edged the lake, and finally plunged my feet into the water. It was very, very cold.

I gasped, but forced my feet to stay submerged. The cold of the water felt important to endure for some reason. Like a cleansing of this very long day.

I glanced back at my family. Abbie was sitting with her legs splayed out while she gnawed on her cob of corn. Hannah was lying on her stomach gazing past me to the sunset. My parents were sitting side by side, both with their legs outstretched and crossed at the ankles, my mom’s head resting on my dad’s shoulder.

There was only one person missing.

My mind swooped to an image of Granly. If she were here right now, she’d be sitting in a folding beach chair. Maybe she’d sip a glass of wine while she searched the sky for the first stars of the night. Or she’d be efficiently packing the dishes up while she gossiped with my mom about old Chicago friends.

But then something surprising happened. Just as quickly as my mind had swooped to Granly, it swooped away again and landed on—the boy from the bookstore.

I wondered what it would be like if he were here on the beach with me. He didn’t seem like the goofy splashing-around-in-the-water type. But I could definitely picture him taking a long, contemplative walk along the lake. Or building a sand castle with me, with all the turrets carefully lined up according to size.

I wondered if he knew the constellations and would point them out as the night sky grew darker. Or maybe he didn’t like to talk much. Maybe he was more of a listener.

I tried to imagine what it might feel like to lean my head against his shoulder or snuggle into those lanky arms. And I remembered the way his face had lit up when he’d smiled at me for the first time.

But after his mom had brought him back down to earth, his face had tightened. His mouth had become a straight, serious line as he’d struggled with the receipt tape and perhaps reviewed a long to-do list of chores in his head.

It had not looked like a kissable mouth.

And those broad shoulders? It seemed there was enough leaning on them already. There w

as no room for my head there.

Even if there was, was Josh thinking about me in the same way?

Was he thinking about me at all? He didn’t even know my name!

I couldn’t stop repeating his name in my head. Josh. I loved the one-syllable simplicity of it. I loved the way it ended with a shhhh that you could draw out, like the soft sizzle of a Lake Michigan wave.

But I stopped myself from whispering the name out loud. If I did, I felt sure that I wouldn’t be able to get it—to get him and my does-he-like-me? angst—out of my head.

So instead I tromped back to my family, who looked blurry and ghostly now that the sun had set.

“Isn’t it time for frozen custard?” I asked.

It was funny that we had so many rituals in Bluepointe, when we had hardly any in LA.

At home we went to whatever brunch spot had the shortest line. Here we might wait for ninety minutes to get Dutch baby pancakes (and only Dutch baby pancakes) at Francie’s Pancake & Waffles.

In LA my mom marked our heights on the laundry room wall whenever she remembered. Not on birthdays or New Years or anything that organized.

But in Bluepointe we always took the exact same photo on the exact same day, which was the last day of our visit. Hannah would kneel in the sand, Abbie would sit next to her, and I would lie on my stomach, my chin on my fists, at the end of the line. We even took that shot in the rain once, because there was no leaving Bluepointe without the “stack of sisters” shot.

Yet another tradition here was frozen custard on our first night in town. We always went to the Blue Moon Custard Stand.

As we drove there Hannah said, “I wonder what color it’s going to be this year.”

The Blue Moon got a new paint job every summer, going from bubble-gum pink to neon yellow to lime green—anything as long as it was ridiculously bright. I guess it was easy to paint, because the stand was no bigger than a backyard shed. There was barely enough room inside for two (small) people to work, and even that looked like a struggle. They always seemed to be elbowing each other away as they took orders, exchanged money, and handed cones through the stand’s one tiny window.

This meant the line was always long and slow-moving, which was part of the fun of the Blue Moon.

Fifteenth Summer

Fifteenth Summer